The MLC Building, North Sydney to be saved — good decision or…?

MLC Building, 105- 153 Miller Street North Sydney Image: Bates, Smart.

The MLC Building, North Sydney, one of Australia’s most significant post-war buildings had been threatened with demolition. On June 2, 2021 Special Minister of State Don Harwin directed the building be listed as an item of state heritage significance after receiving independent advice on a recommendation from the Heritage Council that it should be added to the state heritage register, thwarting plans to raze the block for a multi-million dollar redevelopment.

He said the listing “celebrates the importance of this building to the history of architectural design in NSW and Australia and will provide protection for its heritage values for future generations”

Its birth

In the post-war war period the Mutual Life and Citizens’ Assurance Co. Ltd (MLC) grew rapidly, The Newcastle Sun, (12 August, 1954. p.5).”New Building for M.L.C Company”, reported its assets had grown from £59m - £100m. This rapid growth necessitated a building program to meet its space and customer service needs.

The relationship prospered in the 1950s, with MLC building BSM designed buildings in Brisbane (1955), Wollongong (1956), Shepparton (1959), Ballarat (1954), Geelong (1953), Adelaide (1957), Perth (1957), Newcastle (1957) North Sydney (1957), and Canberra (1959).

The new headquarters building in North Sydney being the principal building of the program. It would house administrative staff and records while executive offices and customer service remained at their Castlereagh Street building.

Mr M.C. Alder the general manager of Mutual Life and Citizens’ Assurance Co. Ltd (MLC) made comments on the need for the new building and its functionality when announcing the company would be constructing its new headquarters on Miller Street, North Sydney.

“‘…the company had bought a site in North Sydney for a new Head Office… The building would be of the latest functional architectural design and would have ample staff amenities.’

Mr Alder said that the company had expanded so much that its building on the corner of Martin Place and Castlereagh Streets would soon be too small to house the staff.

The new North Sydney building would be the beginning of a long-range plan to satisfy its space requirements.

‘The position in the city is becoming intolerable because of traffic congestion as well as the need to accommodate an expanding number of staff.’”

“New head Office for M.L.C” The Sydney Morning Herald (26 March,1954 p9)

Building in North Sydney was ground breaking, North Sydney was residential and small shops, although well served by public transport. At the time there was only other significant office block in North Sydney — an office on Mount Street was being completed for the AMP insurance company. Mr Alder believed in North Sydney making a prescient comment;

“I am of the opinion that in years to come Sydney will be a twin city like Buda and Pest and Brooklyn and New York”

“North Sydney Expansion Continues” The Sydney Morning Herald (21 July,1954 p1)

MLC as an architectural patron

Any history of Australian architecture will include the three Sydney offices built by MLC.

The Martin Place head office designed by Bates Smart and McCutcheon, built in 1938 is one of the finest examples and rare examples of an Art Deco office building in Sydney. Two prominent features are its use of Hawkesbury sandstone, the material of choice for so many of Sydney’s finest buildings, and exceptionally fine stone detailing with Egyptian motif. Its base is red granite from a quarry at Sodwalls, a village 15k from Lithgow.

MLC Headquarters Building, 1938, Castlereagh Street, Sydney.

Jumping forward forty years MLC commissioned Harry Siedler to design the MLC Centre (now named 25 Martin Place) on Martin Place. Completed in 1967 it is a 67 storey octagonal reinforced concrete tower, one of his key works. The building was awarded the Sir John Sulman Medal by Australian Institute of Architects.

The tower and associated plaza conceptualised the notion of integrating generous public space with office and retail areas, parking and open plazas. The tower occupying only 20% of the entire site

MLC Centre (now 25 Martin Place). Image Max Dupain for Seidler Associates

Buildings are just bricks and mortar?

A building is always more or less than the sum of its parts — location, site, purpose, construction, design, budget, client, builder, architect or designer, date, and so the list goes on. All buildings add to the story of our country and who we are…to our history.

Most buildings will be forgotten, razed, rebuilt or renovated, and rightly so. But there are some which must continue to be known and it is important that living buildings not just the records of those buildings continue to form part of our history. It is, I believe, wise to draw wisdom from the past to help us illuminate the present and future. Churchill wrote “Those that fail to learn from history are doomed to repeat it”.

The MLC building North Sydney

MLC Building, North Sydney. Architect: Bates Smart and McCutcheon, 1957. Images: Bates, Smart

To meet MLC’s expansion needs they continued the relationship with architects Bates Smart and McCutcheon (BSM) who were responsible for their existing head office on Castlereagh Street. The North Sydney MLC (Architect Sir Walter McCutcheon) design, a 59 metre-high tower complex in the International Style, was the result, with noted inspiration coming from the Skidmore, Owings & Merrills 1952 Lever House in New York and coming at the same time as the firm's design of ICI House in Melbourne. (Wikpedia).

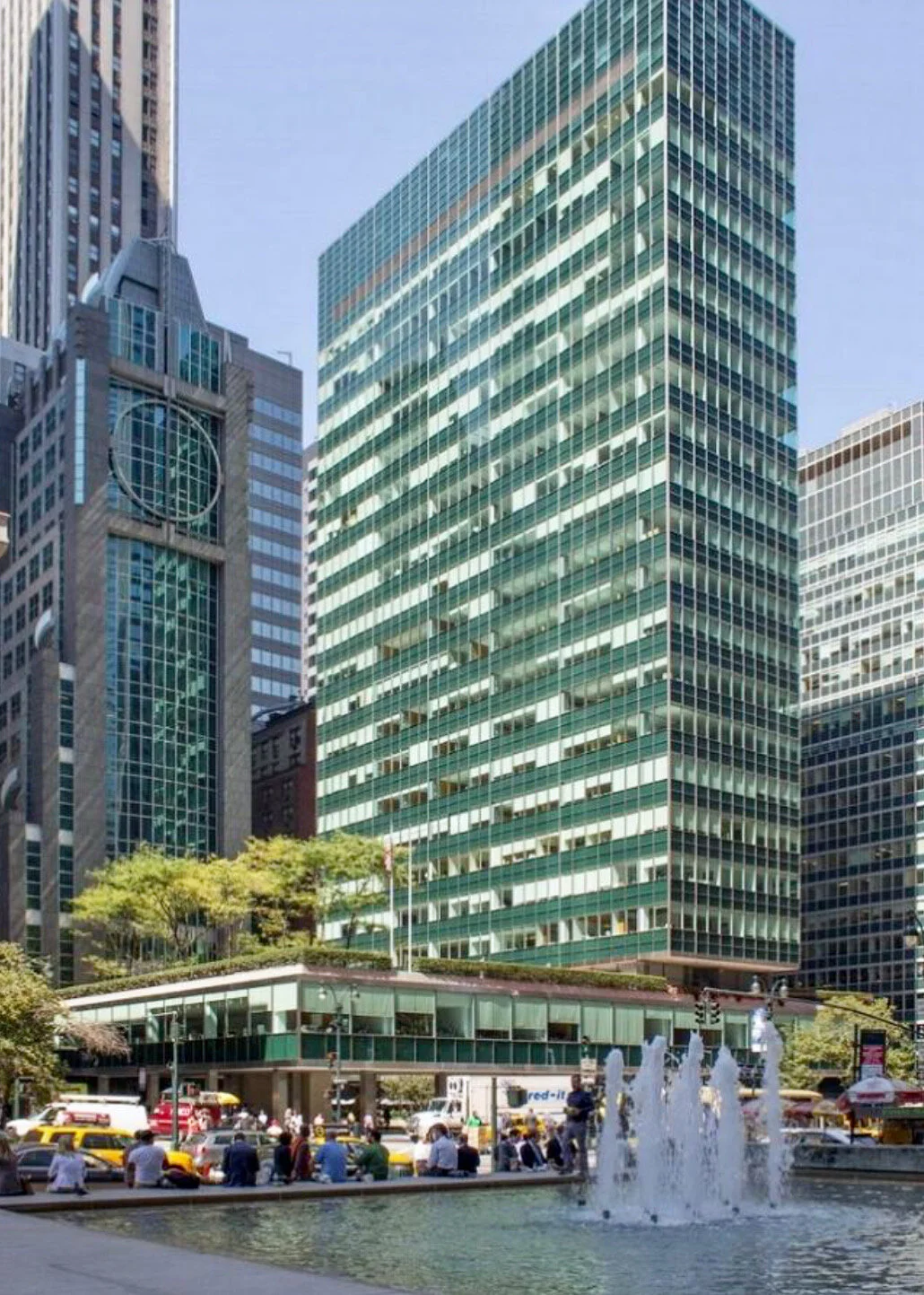

Lever House 1952. 390 Park Avenue, New York. Architect: Skidmore, Owings & Merrill. Image: Wikimapia.

The relationship prospered in the 1950s, with MLC building BSM designed buildings in Brisbane (1955), Wollongong (1956), Shepparton (1959), Ballarat (1954), Geelong (1953), Adelaide (1957), Perth (1957), Newcastle (1957) North Sydney (1957), and Canberra (1959).

Bates Smart Timeline “MLC Building, North Sydney”, Journal March/April 2012

The MLC building North Sydney was…”Completed in 1957 it was the first high rise office block in North Sydney and the largest in Sydney for a number of years after its construction, and is a seminal building associated with the evolution of high-rise office design in Sydney and NSW. It is the earliest surviving curtain wall building in Australia.”

It utilised “construction and structural techniques not previously used in Australia. This includes the first of curtain wall design, the first use of modular units in Australia, fully rigid steel frame structure combined with ‘light weight’ construction of hollow steel floors resulting in reduced construction loads, cost & time. Its significance is also found in its design intention as a people-oriented design with natural light, transparency, and amenity being high in the design considerations”

McCutcheon’s design integrated modern art as an integral part of the buildings design. Works were commissioned by artists Andor Meszros and Gerald Lewers and Gerald and Margo Lewers the designed the forecourt by on the Miller Street frontage

Statement of Significance (extract), NSW Heritage Council Recommendation to the Minister, 5 February 2021 in “MLC BUILDING, NORTH SYDNEY (FORMER) Section 34 Heritage Act 1977 Review Report” 21 April 2021, p 4.

Gerald and Margo Lewers landscaping. Andor Meszros bronze bas relief (Images Heritage NSW)

But who should pay for history?

I am in agreement with the NSW Heritage Council , the Special Minister and the vast majority of submissions that There is no doubt the MLC building is worthy of its heritage listing; North Sydney, Greater Sydney, New South Wales, and Australia all prosper from this decision.

However if there is a cost of retaining the building, maintenance, reduced rents, lower space utilisation these will borne not by the broader population but by the owner — Investa. The obvious question arises; “why should I pay?”, a fair and valid question.

Kathlyn Loseby the NSW President Australian Institute of Architects writes; “A developer or building owner needs to have a viable building, we all need to work together to ensure this is possible. We need to look at incentives for keeping such buildings of significance.”

Kathlyn Loseby, “Why the MLC Building in North Sydney should be saved”, The Fifth Estate 24 September 2020 updated 7 December 2020.

There are a number of ways which can be used to facilitate equity. Examples include the City of Sydney Heritage Floorspace scheme.

“The scheme provides for owners of eligible heritage-listed buildings to be awarded heritage floor space after preparing a conservation management plan and completing agreed conservation works.

The awarded heritage floor space, or HFS, can then be sold to a site that requires it as part of an approved development application. The money raised offsets the cost of conserving the heritage item.” https://www.cityofsydney.nsw.gov.au/cultural-support-funding/heritage-floor-space-scheme

An interesting comparison from 2005 may be made with another International style high-rise building which has also been recognised as special — The Seagram Building, New York.

“The city's Landmarks Preservation Commission has approved the transfer of unused development rights from the venerated Seagram Building on Park Avenue to an adjacent site on Lexington Avenue that will allow for construction of a large hotel and condominium building there.

In return, the owners of the Seagram Building would be required to permanently maintain the exterior of their 50-year-old modernist skyscraper, which is widely regarded as one of the most significant contributions to the urban architecture since World War II, in something close to pristine condition. The 38-story Seagram Building at 53rd Street and Park Avenue was designed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe.

The arrangement "ensures the highest level of protection for the Seagram Building, one of the world's most significant works by a genius of modern architecture, but it also provides New York City with a landmark of the future," said Robert B. Tierney, the Landmarks commission's chairman. The commission approved the deal unanimously on Wednesday after reviewing a plan for the new hotel and condominium tower by Norman Foster, the British architect.”

Lueck, Thomas J. (November 25, 2005). “In Deal for New Tower, Protection for Old One” The New York Times.

Heritage is tricky.

Preserving a great building for future generations is not a simple equation. It must account the needs and interests of all stakeholders, recognise and plan for ongoing maintenance and its funding and more. There is more than one listed and preserved building in Sydney being demolished by the ravages of time and zero use.

The question to ask is — having preserved a building what are the next steps so that it remains relevant from generation to generation?